“Those who do not run away from our pains but touch them with compassion bring healing and new strength. The paradox indeed is that the beginning of healing is in the solidarity with the pain. In our solution oriented society it is more important than ever to realize that wanting to alleviate pain without sharing it is like wanting to save a child from a burning building without the risk of being hurt.”

—Henri Nouwen, from “Reaching Out”

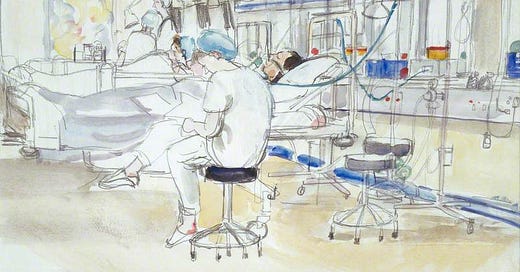

I come again to the page— trying to write something about humanity, grace, and medicine. There are few topics about which I could say more, few topics about which my words seem so inadequate. In my eleven years of work as a bedside nurse, I have seen patterns and attitudes in others and in myself that have filled me with disgust, with contempt for the injustice and corruption in systems of power, in the world, in the human heart. I have been utterly overwhelmed by the senselessness of sickness and affliction. Yet also, I have witnessed moments that are unspeakably precious, unexpected beauty blooming where life is the most desperate and most mundane.

It feels almost unkind to pull back the curtain for those who don’t have an intimate understanding of the complex realities of modern healthcare, and yet it seems almost unfair that others don’t get to see what I see. How do I offer a glimpse into something so wholly grotesque and sacred? Within the realm of human suffering, “There are no unsacred places; / only sacred places / and desecrated places.”1 Anyone in medicine has seen them both.

When I walk into the room—"My whole body an ear, an eye”2—I am attending fully to the body in the bed. I confess I must remind myself at times that it is a body at least; more truly a person. I forget this personhood sometimes, more as the years go by, as the novelty of the work fades away and the machinery of the hospital system churns patients in and out of my hands. With each year my skills and intuitions heighten; with each year my efforts to combat flippancy and cynicism must be re-evaluated, renewed.

I must choose to humanize the being in the bed, to not to dull myself to the constant onslaught of pain, and to seek out beauty for the restoration of my own soul. There are seasons where regrets about my failures to really care for my patients keep me up at night; there are seasons where other stressors leave me empty, where I am all too aware that my best work on any given day will simply not be my most holistic. The repeated, up-close layering of another’s troubles has brought me closer to understanding the lived experience of the patients under my care, yet it has also given me a weathered sort of wisdom in discerning how to appropriately distance myself from their suffering.

The patient is sedated as the neurosurgeon prepares to drill a hole into his skull, inserting a drain to relieve pressure from the bleed in his brain. Just after I push in the medications, the anesthesiologist asks more and more ridiculous questions of the patient, testing his already shoddy level of responsiveness as it wanes into a chemically induced sleep. He’s searching for that threshold where it is appropriate to make the first incision, but we’re all laughing at the Drs antics. The patient is in the crux of a life-altering event—and we’re laughing. I take note of the dissonance. Are we laughing at the patient’s expense? Are we making light of a serious situation? Are we distancing ourselves from the tragedy in front of us so we can calmly save a life? Several hours later the patient is stirring, sedation having worn off, and intracranial pressure drifting towards normalization.

Just across the hall my elderly patient is on a slow trajectory of healing after cardiac surgery, still requiring multiple medications to assist with the squeeze function of his weak heart. Throughout the day his breathing grows increasingly soggy and labored. “Is this normal?” the daughter pulls me aside to ask. I explain that while it is not, I’m not entirely surprised that a patient of his age and constitution isn’t having the elastic bounce-back from surgery that I might expect of a younger person. Forcing myself to step into her perspective, I choose to slow down, walk this non-medical family member through the interventions the team is implementing in a language she can understand, giving voice to what tempered reassurances I’m 1000% positive I can offer. I find myself saying the words I repeat almost daily: “We have to take this one day at a time.” Nobody wants to hear that. People want guarantees, not to sit with uncertainty in the disturbing reality that we live in a constant state of limbo.

“My daughter’s never seen me like this before,” the patient tells me. Then he looks at her: “I hope you never see me like this again!” The statement lands in my ears like the fable of King Canute commanding the tide to halt before him—it is utter foolishness. We do not age in reverse, dear sir, I think. Next time, you will likely look much worse. I keep these sobering judgements to myself. The next day the patient is clearly improving, just as I presumed but could not promise. We begin weaning some medications, leaning hard into the most essential and infuriating ingredient of healing: time.

In a world filled with wars and rumors of wars, pandemics and substance use disorders, mental health crises and gun violence, it surprises me when people are surprised by the inevitability of death. The presumption that medicine is magic remains pervasive. Aren’t doctors and nurses supposed to be miracle workers? Hasn’t science evolved to extend life further and further? And yet death comes for us all; dust returns to dust.

My work serves as a near constant memento mori, a reminder that “Life comes from God and life is precious precisely because it is brief.”3 Each person, each patient holds a lifetime of history leading up to the instant they land in my care. I’m honored to bear witness to some of their most vulnerable moments, and also acutely aware of my limitations as just one person swimming in this complex industry of suffering. The brevity of life can be compressed into any given 12 hour shift, leaving me teetering on the precipice between tragedy and hallowed ground. How often I wish others outside of this realm could feel that righteous gravity, and yet I find myself working to shield them from the weight of it.

If only our modern Western society did not live, “in ‘denial of death.’ [Death] only enters our imaginations in worst case scenarios…. The more we fight time and death, the harder they’ll fight us.”4 Even in the worst case scenarios, people often presume that death is optional, a last resort for when all else fails. How do we learn to face it, even as we hate it? How do we choose reverence and dignity, even while wrestling with its cruelty? I do not have answers, I only know that so many avoid asking such questions until far too late. To move towards mortality, whether our own or that of another, with both compassion and clarity is both costly and uncomfortable, and yet— strangely freeing. It will not not leave us unchanged, but wiser for having reckoned with both our finitude and the wild goodness of our inherent value.

I keep my head on as I enter each room, making space for grief, humor, and little bits of relief. Ideally, I walk in with approachable authority, with soft edges accessible and ripe for empathy. And yet how I step into each room is something of a facade because I never know how each patient will effect me— I only know that if I’m doing my job right, I won’t leave the room entirely unscathed, though I may not recognize how until later.

From “How to be a Poet,” by Wendell Berry

From “The Simple Dark,” by Luci Shaw

From “The Covenant of Water,” by Dr. Abraham Verghese

Fellow nurse here. Stepped away from the bedside after 8 years in Oncology/Hospice in order to be home with my children full-time. It’s been one year out of patient care but reading this takes me right back into those sacred moments. Words and thoughts and holding the pain of another - emotionally and physically - only known to myself, my patients, and the Lord who alone gives life.

Your story about the incongruity of laughter at the moment of sedation is a perfect illustration of the struggle between self-preservation (you’re watching a human skill being drilled into) and respect for the humanity of another. I am thankful I got to spend time in my specialty because maintaining dignity was always of considerable importance. We didn’t do it perfectly, but it was at least a shared value throughout the hierarchy.

Thank you so much for this. You give voice to the gravity of our work, which many among us cannot articulate even mentally. You are a gift to your patients, I am sure of it.

Beautifully written Becca. Thanks for sharing your thoughts. ❤️